Thinking In Lists

Have you ever tried playing chess against yourself? Unless you are a chess purist or have a split personality, it is not much fun.

The pleasure of engaging in a game like chess comes from challenging another mind (human or otherwise). From not knowing what the other is planning and the uncertainty that comes with it. When two opponents share the same brain, there are no secrets or surprises.

Another player makes the game “real.” When you have found a weakness in the opposing position and hatch a plan to exploit it, your opponent will prove your plot right or wrong. The stronger the rival, the harder your ideas will be tested. Left alone, that “clash with reality” can’t occur. You can try hard to emulate both separate sides, but as the two are coming from the same mind, all you do is evaluate yourself, which has limited value.

We are in a similar predicament every time we are trying to understand something or come up with an explanation. Because we are the creator of our thoughts as well as their recipient, we are biting our own tails whenever we try to figure out if what we think is correct or not.

To overcome the lack of outside perspective, we intend to look at a problem from all angles. The trouble is that not only is seeing the forest from the trees difficult, but that thinking itself is flawed. The mind’s default operational mode is not rationality, and it has no incentive to spot inconsistencies. Instead, it happily paints over blind spots, leaving us unaware of our imperfections.

Why is this so? Wouldn’t it be beneficial to our species to ensure that our thinking is consistent and flawless? The short answer is no. The mind is not designed to think.1 From an evolutionary point of view, it is more beneficial for our survival to automate thinking as much as possible. Active, hard pondering of problems consumes valuable energy that would be better spent on spotting danger or other life-preserving activities.

The brain is arguably the most wonderful thing in the universe (as far as we know, that is). It can do marvelous things like seeing, hearing, memorizing, beating a heart, all at the same time and while giving birth to consciousness. But when it comes to learning and rational reasoning, the organ inside our skull is a broken tool, like a water bucket with holes.

Without a clear picture of what we actually think (rather than what we believe to think), efficient learning is difficult. It is essential to shine a bright light on the gaps in our reasoning and bring them out into the open. Learning is as much about gaining new insights as it is about getting rid of false beliefs.

What can we do?

Ideally, you’d have a few like-minded people at your disposal interested in your stuff who could challenge and inspire you (could this be an AI in the future? That would be tremendous).

Lacking such a sophisticated support group, the next best thing to do is to break the mind’s self-evaluation-loop by putting distance between the moment we generate an idea and the time we evaluate it.

Humanity has invented a tool for exactly that problem - pen and paper. Writing helps us capture our fuzzy thoughts and make them explicit and observable. The problem is it can be a laborious word-wrangling exercise to express ourselves. Luckily, for our purposes, we can skip most of the arduous parts of translating our intentions into sentences and simply transpose our raw thoughts onto paper. This can be done much easier and faster by making a list.

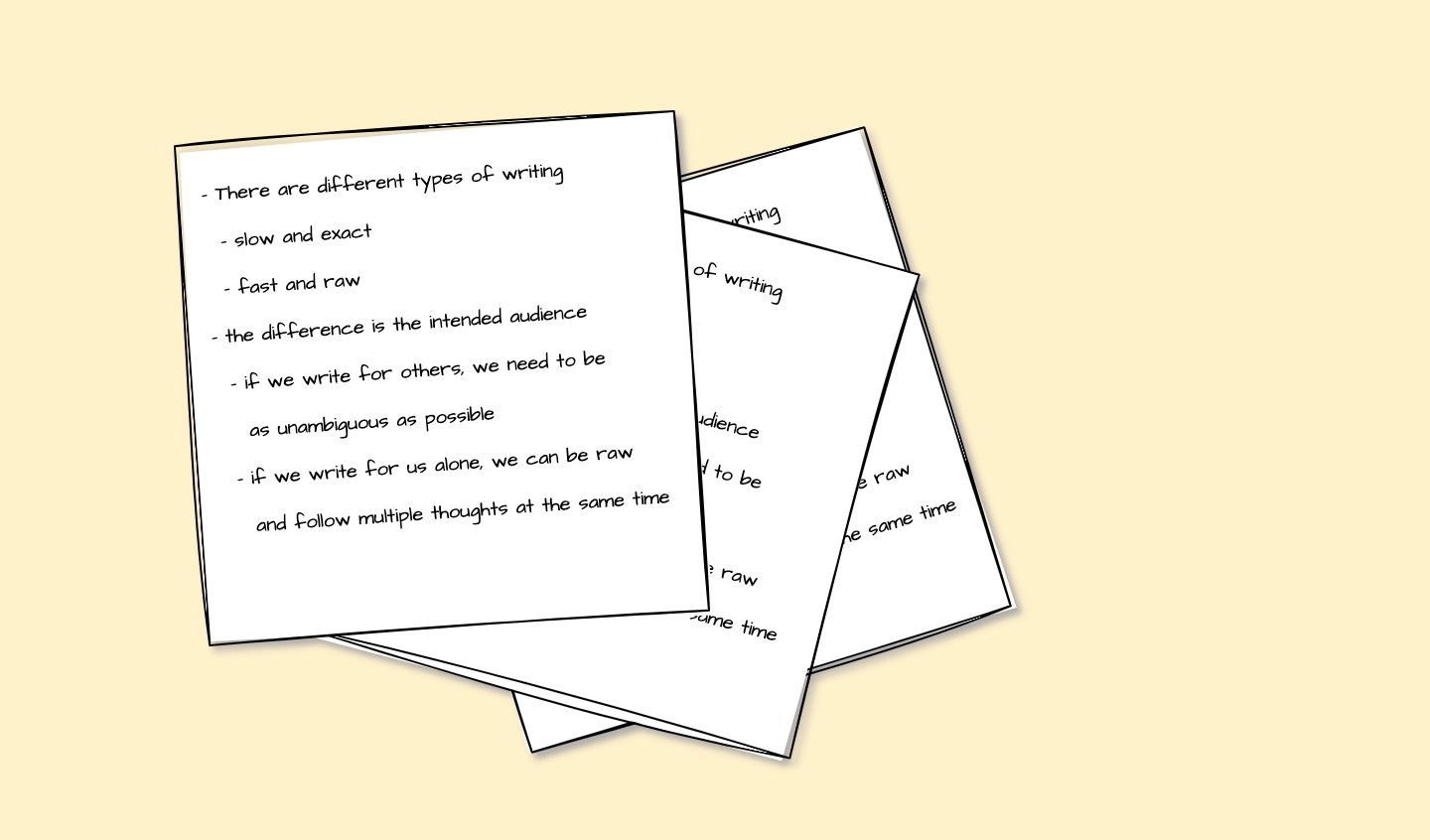

The difference between a list and “normal” writing is the intended audience. Usually, we write for others, which makes it so hard because the reader does not know anything about us. We need to give as much context and be exact as possible to avoid ambiguity. The list, on the other hand, is only meant to be read by the author. No need to explain where we are coming from; we can be as esoteric in our descriptions as we like.

There is one non-negotiable requirement, though: Everything on the list has to be written using our very own words. This is crucial to make the list fulfill its purpose.

Looking up answers and copying-pasting them into our list does not help at all - rather the opposite, it only strengthens the gaps in our understanding because it creates the illusion of knowledge. We may write down correct facts, but they are not coming from us.

This is one reason why highlighting passages in a book does very little to increase comprehension of a text. It looks like learning because the passages are important, but they are not our words, they are expressions of someone else’s thinking (underlining text passages can still be a useful activity, but the highlights are merely bookmarks, helping navigate a large amount of information).

Definitions, buzzwords, or concepts we don’t fully grasp don’t belong on the list. Unless we write down precisely this - that we don’t understand those terms (e.g., “Technology X is a distributed-self-contained management system - what the heck does that mean?”)

We list what we know (or believe to know) and what we don’t know or understand. This is a fast and fluent exercise. It does not require much thinking. Then, very soon, we will have exhausted what’s on our mind.

I love making lists. Whenever I am stuck, I start listing my thoughts. This post here started as a list (as all others have) that I then successively transformed into full sentences. The moment I got stuck, I switched back into list mode, and so forth. I’m always shifting modes. From slow and exact writing, building up a single line of argument, to the immediate and quick jotting down of multiple strands of thoughts (there are other modes, but that’s a subject for another post).

When I begin a new task, I start with a list. To clarify my intentions and beliefs and to prepare myself for the work ahead by bringing into focus the things I’m sure about and those I’m not. This way, I prime my mind to find answers for the gaps I have and to look for confirmation of what I assume to be true.

Lists are helpful for any kind of mental task. They expand our short-term memory. They force us to think sequentially and turn vagueness into explicitness. And list-making is a fun activity, even relaxing, similar to meditation with its benefits, where we step back from being mindlessly captured by thoughts and instead gain control through observing our mental states.